This year’s Christmas Bird Count (CBC) marks the 117th anniversary. Ornithologist Frank Chapman founded the event in 1900. Before then, hunters spent their Christmases competing to hunt and collect as many birds as they could. Chapman had an idea: Why not…count birds instead of killing them? Today, the CBC is the largest and longest running citizen science program, conducted by the National Audubon Society. Counts around North, Central, and South America occur from mid-December to early January. You can count birds all day long – from pre-dawn to dusk – or simply contribute as few as 15 minutes of your time. Each area is divided by circles of 15-mile diameters, in which groups are assigned to different territories. Circle compilers combine each group’s list. These lists eventually make their way to ornithologists and conservation biologists who utilize the lists to study bird behavior and the environment. (For information regarding on how to join the count, please see this web page.)

On December 17th, I participated in my 3rd Peekskill count, again assigned to the Ossining territory with Charlie Roberto and Christine McCluskey. I was supposed to meet Charlie and Christine at 7AM to carpool. But the weather forecast predicted 3-5 inches of snow between 4 and 11AM. Seeing snow having already accumulated on my street at 6, I went back to bed. Waiting until the snow nearly stopped falling seemed prudent.

My street at 9AM. It was still coming down. © S.G. Hansen

My house is located deep in residential area. I live on a cul-de-sac that branches off a larger cul-de-sac. The plows seem to clean my street later than everywhere else. Today, the plow came shortly after 6, and then once more two hours later. By the time I finished cleaning the car and the bottom of my driveway at 11, a bit of frozen rain began to fall. A couple inches of snow yet coated my street. Who knew when the plow would come again? I got going to the new meet-up place, Maryknoll.

At the intersection with the main local road, I felt nervousness turn into dread. I thought the roads would be more clear. The amount of snow and slush looked troubling. I had to turn left. That meant driving downhill. I barely made the turn when my 4-wheel drive station wagon started sliding down and around. I wound up on the other lane, perpendicular to the road. I righted myself and pressed forward.

I parked at Maryknoll with much relief. No precipitation was falling. As I waited for Christine and Charlie to pick me up, I counted 7 European Starling and 3 American Crow. When they arrived, we ended up not birding much. Only a Carolina Wren responded to Charlie’s raspy pishing.

We went to the Mariandale Retreat and Conference Center to meet up with Kyle and count ducks. Mariandale overlooks the Hudson River – ideal for winter waterfowl-watching. On our way to the look-out, I heard chickadees buzzing. Charlie had said earlier that they didn’t get many kinglets – neither ruby- nor golden-crowned – so I lagged behind to pish. (Kinglets like to join chickadees and titmice in order to easily find food.) No kinglets. I did get us our first and only Brown Creeper ( Only one other person assigned to Ossining had creepers, just 2.).

We observed 2 Mallards; small rafts of Ruddy Duck, Bufflehead and Canada Goose; and larger rafts of Common Mergansers (100+) and Canvasback (100+). Without binoculars, the rafts looked like dots bunched together in a pointillist painting. Kyle spotted 1 LONG-TAILED DUCK, 5 COMMON GOLDENEYE, 17 GREATER SCAUP, and 2 REDHEAD. (Additionally, Charlie and Kyle counted 22 Scaup sp. – meaning that they identified these ducks as far enough as being scaup, but whether Greater or Lesser was undetermined.)

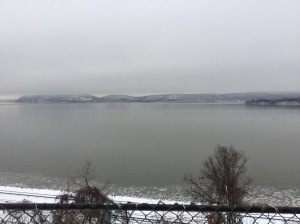

Our view from Mariandale. You can see the point of Croton Point Park on the right. © S.G. Hansen

Once finished, Charlie, Christine and I left Mariandale, separating from Kyle. We then drove up to the Ossining-Cortlandt Manor boundary by way of Quaker Ridge Road. We parked at the side of the road. Pishing got us the winter usuals, plus 2 beautifully bright Fox Sparrows. Charlie said that he’d gotten Common Redpolls there before (Common Redpolls don’t often migrate to Westchester in the winter unless a shortage of food causes their eruption).

Out next stop was Croton Dam for more waterfowl. Seconds after we turned onto Croton Dam Road, Charlie spotted a Pileated Woodpecker. He directed Christine to make a u-turn and drive back very slowly. Christine inched forward. We lowered our windows, inviting in 20° air. I kept my eyes peeled for a black blob stuck on a tree far into the woods. Christine suddenly stopped. It took me a second to see that the Pileated was only fifteen feet away from the road, foraging on a short snag.

We watched in careful silence. I’m always in awe of a Pileated’s size at every chance I see one. They grow up to 17 inches tall. I found it incredible they are larger than certain hawks! The red mustache (the line by the bill) on this Pileated indicated he was male. His feet looked so large and much like a raptor’s, scaly and sharp. His tail feathers – which propped him against the trunk – looked incredibly strong. He banged his beak against the wood. Thudthudthudthud. His vibrant yellow eyes remained wide open. Bits of wood fell. He eventually created a small rectangular hole, from which he uncovered food, probably hibernating insects.

As Christine and I took photographs and videos, a Northern Flicker colorfully bombed the scene. He (black mustache – female flickers don’t have one) first landed on a nearby tree. Because of the below-freezing temperature, he was so puffed up that he looked like the Audubon plush version of himself. A few seconds later, he flitted onto the snag. As he skulked around the trunk, in and out of our view, he watched the Pileated. He hoped to seize food when the larger woodpecker appeared distracted. The Pileated ignored the flicker.

“Do you think he’ll share?” the Northern Flicker asks us as he watches the Pileated Woodpecker. © Christine McCluskey

I couldn’t tell if the flicker was tentative or delicately biding his time for the perfect moment. Finally, he crept too closely, and the Pileated aggressively nudged his beak towards the smaller woodpecker. The flicker flew to another tree only to return to the snag a short moment later. He skulked around some more and hid himself, much to Christine’s frustration. The Pileated paid no mind. He continued pecking and eating.

The flicker made a move again. The Pileated charged at him, scaring him enough that he flew away for good.

The Pileated went about his business.We watched him a bit more, but we had to move on to the Croton Dam. Only three hours of daylight remained.

Charlie looking through his scope at the Croton Dam. © S.G. Hansen

Charlie and I studying the Lesser Scaup. © Christine McCluskey

There, we observed more Mallards and Buffleheads. In addition, we added American Black Duck, Gadwall, 2 Lesser Scaup, Hooded Mergansers, and Mute Swan to our species list. For non-waterfowl, we tallied 2 Greater Cormorant fishing and 1 rattling Belted Kingfisher. We also got 1 flyover adult Bald Eagle, surprisingly our only eagle for the day.

We then drove around the reservoir – my favorite part of the count. The plow had yet to clean Croton Lake Road. Other cars had already driven through, as evident from the tire tracks. Christine had an easier time driving than during past counts. The snow had filled up the numerous pot holes. We didn’t skid once.

As we surveyed the shoreline for waterfowl, I absorbed our first fresh winterscape of the season. Weak sunlight brightened the ubiquitous stark-white snow, which outlined the skeleton trees. The water reflected the sky’s gentle gray. Light rain began to fall. Thousands of little ripples textured the silvery water.

We frequently came across small groups of Mallards, Black Ducks, Buffleheads, and Pied-billed Grebes along the water’s edge. At one location, we found one large raft of waterfowl by an island, where we counted many more Canada Goose, Mallards, Buffleheads, black ducks, Hooded Mergansers, and Mute Swan. We also saw a dozen Ring-necked Ducks and – a good duck for the count – 5 American Wigeon. All in all, hundreds of waterfowl were present.

In the middle of Charlie’s counting, we heard a roaring noise approach. A snow plow was coming. To our dismay, every duck took off as soon the truck passed by, leaving the geese and the swans. Charlie had to estimate the numbers of each duck species as they flew, but he was able to count the Ring-necked Ducks and wigeons, fortunately.

Under the Taconic bridges, we got three more species: 2 huddling Great Blue Herons, 1 Double-crested Cormorant, and 1 Common Loon.

Once we concluded the reservoir tour, Charlie needed to leave to start preparing for the compilation dinner. After Christine and I dropped him off at his car, we headed to Sundial Farm, which has good field and brush habitat. We flushed a Red-tailed Hawk as we walked toward the back field.

On the other side of the fence foraged a flock of more than 40 juncos. Though we had seen more than a hundred already, I was excited to see a larger flock – juncos are one of the common birds I enjoy watching no matter what (as proven in a previous post of mine). Curiously, some of them were hopping up and down. I thought they were performing part of a mating ritual, similar to that of the Sandhill Crane. Looking more closely, I realized they were hopping onto the reeds and riding the stalks down to the ground, taking the seeds with them. [I unfortunately can’t upload my video on WordPress. I did post it on Facebook.]

Aside from the Red-tail and the jumping juncos, we didn’t have else much. We heard a White-breasted Nuthatch and a Downy Woodpecker. Pishing only brought in chickadees, titmice, a few White-throated Sparrows, and some juncos.

With less than an hour of daylight left, the birds must have decided to retire early. Our last stops were the Hudson Hills Golf Course, a cul-de-sac that yielded a good number of birds for last year’s count, and Maryknoll again to drop me off at my car. We hardly found more birds at any of these locations. Pishing produced nothing much. 75 European starlings. A few more chickadees, juncos, and white-throated sparrows. A cardinal, a crow, a Carolina Wren and a Northern Mockingbird.

Christine and I had enough of the cold and the lack of bird activity. So we headed over to Teatown for the compilation dinner.

Other Ossining specials were PINE WARBLER, COMMON YELLOWTHROAT, RED-BREASTED NUTHATCH. One Peekskill group hilariously had a NORTHERN PARULA in front of the Peekskill Brewery (after or before beer?), hanging with Yellow-rumped Warblers.

If you would like to see more of Christine’s photographs from the count, visit her Flickr page here! She also uploaded fantastic videos of the Pileated Woodpecker and the Northern Flicker.